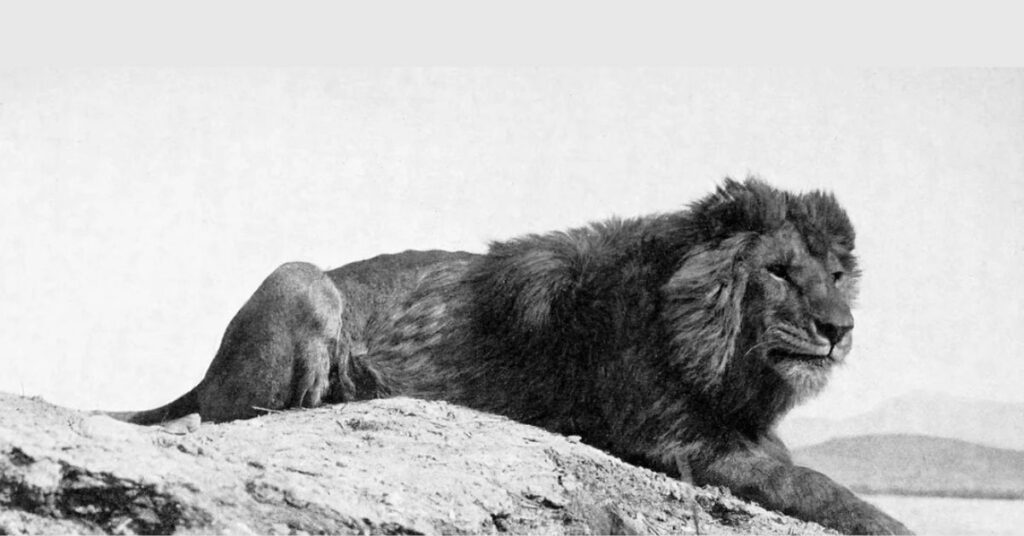

Last Photo of the Barbary LionOne of the most potent and eerie animal photos in history is the famous aerial portrait of the Barbary lion taken in 1925 by French photographer Marcelin Flandrin. This image of a lone lion against a bleak mountain backdrop, taken during a fly over Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, has come to represent extinction. It captures a last moment of existence before a proud species vanished from the wild forever and is widely regarded as the last known photograph of a Barbary lion in the wild. It is more than just a historical picture; it is a silent reminder of the frailty of nature and the part that humans play in either preserving or destroying it.

Who Was Marcelin Flandrin?

Early in the 20th century, French military photographer and postcard publisher Marcelin Flandrin made a lot of work in North Africa. Flandrin, who is well-known for his aerial photography and powerful portrayals of colonial Morocco, captured everything from military outposts to cityscapes. In 1925, while flying from Casablanca to Dakar, he took what would turn out to be the last photograph of a Barbary lion in the wild. Flandrin was unaware that his image would later represent the demise of one of the most majestic lion subspecies in history. Today, his name will always be connected to the Barbary lion’s last chapter.

Historical Range and Biology of the Barbary Lion

The Barbary lion, sometimes referred to as the Atlas or North African lion, used to traverse the large Maghreb region, which includes portions of Libya and Egypt as well as Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. North of the Sahara, these lions lived in broad plains, mountain ranges, and thick woods. Males could weigh up to 230 kg (more than 500 pounds), and occasionally even more, making them larger than the majority of other lion subspecies. Their enormous dark mane, which ran down the chest, over the shoulders, and occasionally around the belly, was one of their defining characteristics. They were the most magnificent lions in history because of their strong physique and distinctive look.

Berber tribes held Barbary lions in high regard and even kept them in Roman arenas where they faced off against gladiators and other animals. In addition to being the top predators in their environments, they served as significant regional symbols of power and distinction. Their extinction in the wild was a cultural and historical catastrophe in addition to a loss of biodiversity.

The Road to Extinction: A Tragic Timeline

It took time for the Barbary lion to go extinct in the wild. Hunting, habitat damage, and human involvement all contributed to the protracted and agonizing process. Due to extensive deforestation, a decline in prey, and the growing accessibility of weapons, their numbers had already started to decline by the 19th century. Conflict was unavoidable when human settlements grew into lion habitats. Colonial authorities even provided bounties for slain lions, which were killed to protect livestock.

Barbary lions had become increasingly rare by the early 1900s. The last verified killing of a wild Barbary lion took place in Morocco in 1942, while the last commonly recognized photograph of a wild species was taken in 1925. The majority of scientists concur that the Barbary lion was extinct in the wild by the 1960s, despite a few unverified sightings that were claimed in Algeria in the 1950s. Their survival was impossible due to a combination of fragmented populations, overhunting, and diminishing habitats.

The Power of the Photograph

The emotional significance of Flandrin’s 1925 photo is more significant than its rarity. The image depicts a solitary lion traversing a desolate area, encircled by expansive and harsh terrain. The image’s loneliness reflects the lion’s actual destiny: a magnificent creature reduced to a lone soul stumbling through a desolate wilderness, oblivious to the fact that it would soon be the last of its kind to be immortalized on film.

Historians, conservationists, and regular viewers have all expressed strong emotions in response to the picture. Many first-time viewers describe it as eerie, lovely, and incredibly depressing. It has received a lot of social media shares, frequently with heartfelt, apologetic, or respectful messages. It acts as a potent visual reminder of the price of conservation inaction.

Authenticity and Controversy

Some doubters have cast doubt on the 1925 photo’s veracity throughout time. They contend that the picture might have been manufactured or even changed, or that the lion seems to be positioned too precisely. Nonetheless, professionals who are acquainted with Flandrin’s work and photography techniques have attested to the authenticity of the image. The grain, camera, and angle match those of previous Flandrin photographs from that period. Additional credibility is added by archival data that confirm he flew over the Atlas Mountains at the relevant time.

Most significantly, the photograph is universally regarded as authentic by biologists and historians. It still shows up in scientific journals, museum displays, and instructional resources about extinct and endangered species. The significance of the picture is unaffected, even if there is still some uncertainty surrounding it.

The Legacy Lives On: Captive Descendants

The Barbary lion is no longer found in the wild, but its genetic heritage endures in captivity, mostly in lions owned by Moroccan aristocrats. Lions were maintained in palace menageries by Moroccan sultans for generations because they were seen as protective and powerful symbols. In an effort to maintain the line, environmentalists started overseeing breeding procedures at Rabat Zoo when these lions, thought to be of pure Barbary origin, were transferred there.

Although none of the 80–100 lions that exist now are genetically pure, they are thought to be descended from the first Barbary lions. Although these lions belong to the northern lion subspecies (Panthera leo leo), DNA analysis has revealed that their precise genetic composition is mixed. Nevertheless, as representatives of their extinct species, environmentalists are striving to save these lions.

ancestors, using selective breeding and careful lineage tracking to maintain as much of the original bloodline as possible.

Conservation Lessons for the Future

The story of the Barbary lion is a cautionary tale for conservation efforts worldwide. It teaches us several critical lessons:

- Extinction is often silent and gradual – Species don’t vanish overnight; they slowly disappear while the world watches without noticing.

- Captive populations are vital – Even if the wild population is lost, animals in captivity can carry the species’ legacy forward.

- Visual storytelling is powerful – A single image can ignite global awareness and mobilize action.

- Human responsibility is undeniable – Habitat destruction, hunting, and ignorance all played a role in the Barbary lion’s extinction, and similar patterns are repeating with modern species today.

The Barbary lion’s disappearance should galvanize action to protect the lions of Central, West, and East Africa, many of which are now facing similar threats from poaching, habitat loss, and human-wildlife conflict.

Final Thoughts About Last Photo of the Barbary Lion

More than just a predator, the Barbary lion represented strength, culture, and the untamed grandeur of North Africa. The final image captured in 1925 captures a moment of worldwide loss in addition to a rare animal. The Barbary lion is still communicating with us through this picture, alerting us to the negative effects of unbridled abuse and disregard.